Kunié Sugiura’s boundary-defying engagement with the photographic medium has yet to receive the attention it deserves. In this interview, she shares her thoughts on her six-decade career, her unending fascination with photography’s fluidity, and the thrill of the first major U.S. survey of her work.

SFMOMA: This is your first major U.S. exhibition. What does this mean at this stage of your career?

Kunié Sugiura: I am very happy I found a way of life that has interested me and has kept my focus for so long. Over my career, I have had a few people and audiences who have supported my art. This time, I feel like more people are understanding my ideas and art. To me, art is a visual lineage, like A to B to C to D, and I’m finally part of this system. I’m very honored to be a part of it.

SFMOMA: What drew you to art?

KS: In eighth grade, I had a teacher who took us to a cherry blossom park and asked us to paint the flowers. They looked like fog and I didn’t know what to do. I saw this big, old pine tree that I could paint, so I put it in the center and put pink all around it. I was sure he would be disappointed, but he picked up my piece and said, “This is a masterwork.” I did not like school, but in art class I could be free and liberated.

SFMOMA: How did you get into photography?

KS: I was a science major. In 1960s Japan, science was not a desirable profession for women, even if you got the highest education. You could not expect acceptance from society. So, I started thinking of a rescue plan. Fortunately, I met this woman who told me about a very good school in Chicago that accepted foreign students. After months of preparation, I applied to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and they accepted me. I was 20. That changed my life. During the first year, we studied a different medium every six weeks — welding, ceramic, weaving, and, one time, it was photography. Kenneth Josephson taught a class on photograms and pinhole cameras.

At the end of the first year, we had to choose an area of study. Two teachers invited me to major in fine art photography. The ceramics teacher also liked me, but I didn’t like clay going into my nails, so I chose photography.

SFMOMA: Was it hard to convince your mother to let you come to the U.S. in 1960?

KS: Not at all. My mother worked in a supermarket on an army base in the suburbs of Tokyo, so she met lots of American military families. We loved these people. My mother visited friends in Hawaii and Wisconsin and when she came back she said she would be happy to help me go to America because it is a wonderful country. I didn’t have a father at home; my mother, grandmother, and aunt were very independent women.

SFMOMA: How has being a Japanese national living in the U.S. impacted your work?

KS: Anybody who leaves their home country starts to see it from a different perspective. In Chicago, people would ask, “Are you Buddhist? Are you Zen?” Something I would never think of in Japan because it is a very homogenous culture and almost all are Buddhist. It is not only physical alienation, but you become analytical about yourself and your culture.

SFMOMA: What have been the greatest influences on your art?

KS: In 1962, Pop and Minimal art were happening. The first time I saw Andy Warhol, people were saying, “That’s not art.” We all loved the Abstract Expressionists, and expected their works to keep coming, but suddenly things changed. I realized that’s the way art making should be — always something new taking over something established.

When I moved to New York City’s Chinatown I met all these artists. My neighbor downstairs knew Keith Sonnier and Jackie Winsor. Gordon Matta-Clark was a good friend. My upstairs neighbor John Duff was good friends with Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly. The whole New York art world was presented to me. I’d go to the bank and see Marisol there, and James Rosenquist walking his dog. SoHo was starting to happen and Leo Castelli gallery.

SFMOMA: You have always found new ways to mix photography with other mediums: painting, sculpture, installation. What draws you to these combinations?

KS: In my last year of school, I was making color photographs with very experimental techniques and progressive concepts, but people didn’t think of me as a serious artist. At that time, size mattered. In photography, we were not making large prints like now, so I had to make a change. I thought, “an image on canvas doesn’t have to be only painting, but if it’s on canvas and a large size, people automatically think it’s a painting.” That’s when I started photopainting.

SFMOMA: What is a common theme in your work?

KS: An affinity to nature. When I moved to New York, I didn’t take pictures of cars, people, or houses. I went to the park or beach and took pictures of stones and flowers and leaves. Virginia Heckert, a photography curator, said those things probably reminded me of Japan. Japanese artists try to be in harmony with nature, to get inside and understand a thing, then express something about it.

SFMOMA: Why photography?

KS: I always want to be unique and not follow other people. I also like to be involved physically and to visually express things through different techniques. Photography is perfect for that.

Photography relates to regular life, sports, commerce, fashion, journalism, and politics. It is truth but can also be fake; simple but complicated. This is a medium we can use to visualize our real life. Before, photography was single images, now it can be an image with a sentence explaining it or streaming. It keeps changing so we don’t really know what photography is; that’s what fascinates me.

THE ARTIST ON SIX WORKS

Experimental Work: Cko number 05 (1967)

This is one of 100 Cko pieces I made during my final year of art school. The instigation was seeing Perspective of Nude by Bill Brandt, an English photographer who documented the working class. Instead of an erotic nude, he made a story about a woman’s life or what she was thinking.

Brandt used a wide-angle lens, an architectural lens that puts a focus on everything. I went with a fisheye lens which is the most extreme wide-angle, 360 degrees in focus. It’s round if you are shooting from far away; up close, you get this oval shape. In the standard print process, the edges are black, but I sometimes process them halfway so they’re brownish.

Around that time I also saw Eikoh Hosoe’s photographs in Barakei: Ordeal by Roses, a photobook with text by the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima, the Japanese writer. It made me understand that photography doesn’t have to be objective, it could be a story. I wanted to express the isolation I felt, and I was reading about existentialism. I thought I could express both using this color photography experiment.

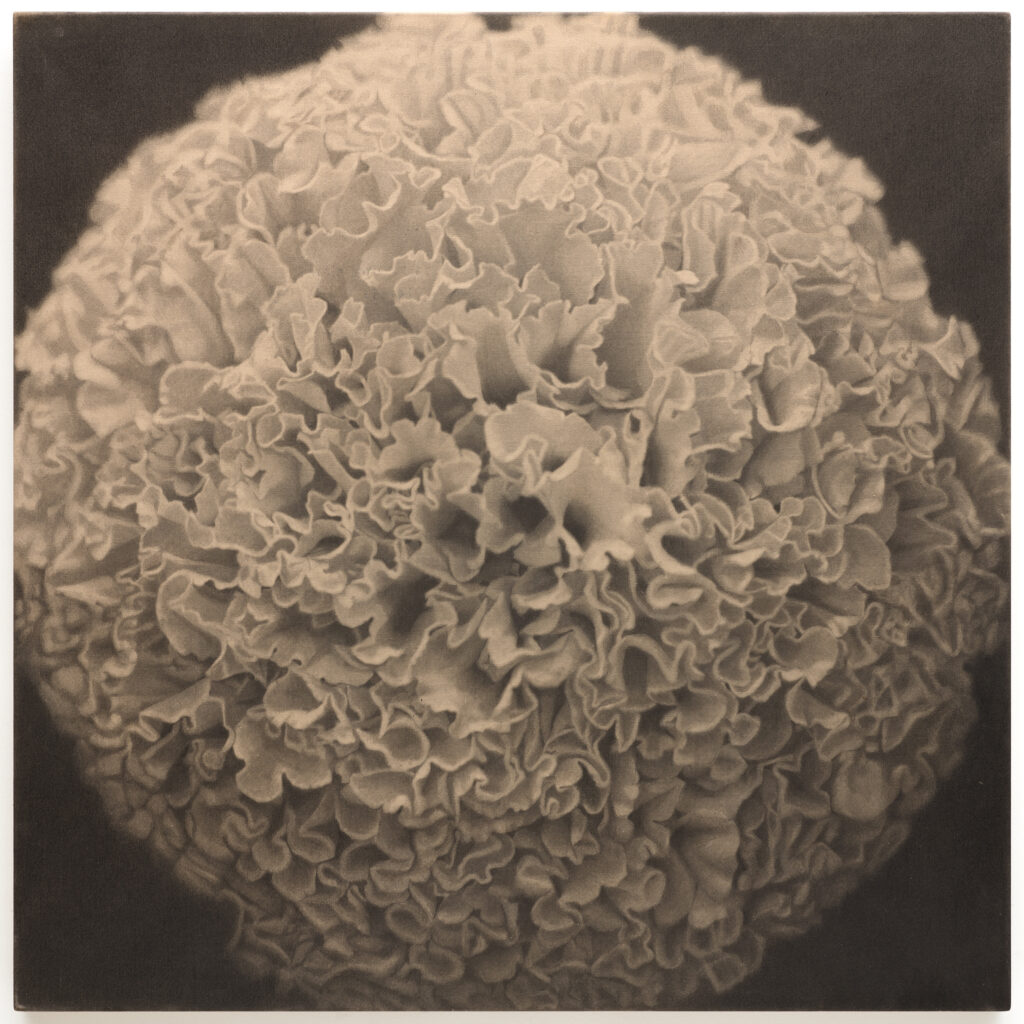

Large Photo Emulsion on Canvas: Yellow Mum (1969)

I used the close-up ring on my camera so I could go very near and fill the frame with one flower.

Making prints in a very large size, some six-by-eight feet, creates a different reality. Small pebbles, for instance, become large universal images. Photo emulsion is applied on raw canvas, and white looks beige-ish and black is not really black. I started using pencil or black acrylic on the prints to create more contrast and make the image crisper.

I think like an Impressionist painter. I like how images in groupings or series, for instance a seashell or flower from different angles, can show different characteristics. With painting this takes forever, but you can do this very easily with photography.

Artist Portraits: After Electric Dress Ap, Pink (2001–2002)

This work was inspired by avant-garde Japanese artist Atsuko Tanaka who made an armature in the 1950s using electric light bulbs or ornaments. It was so beautiful — bright red, blue, and yellow. I couldn’t forget it, so I tried to do my own. My mother was throwing out Christmas lights, so I wrapped them around my friend’s body, and made the piece After Electric Dress. This was my spontaneous homage to Atsuko Tanaka, and also a sort of portrait that references her artwork name in the title.

Sculptural Work: Racks (1994)

This installation came about when I took home postcard racks a store had thrown out. At the time I was doing work with X-ray film, so I put them together. The X-rays hanging on a rack were like a jigsaw puzzle. It suggested movement and the configuration could keep changing. I like to express the unknown and unexpected as a part of my work. I had also recently seen photographs of DNA from the scientists Watson and Crick. I thought my rack pieces with the X-rays superficially resembled the double helix structure of DNA.

I began using X-rays after I got a collapsed lung and had lots of X-rays taken. The doctor said they threw the films out after three years, so I asked for mine and they gave them to me with two boxes of other people’s X-rays. Friends would give me theirs, too.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I found X-rays I hadn’t used so I made a new photo painting, Vertebrae. I printed photos of X-rays on canvas and added color chart panels. Vertebrae X-rays usually mean a physical problem while visualizing color involves light and light is a necessary element for life. So it’s death and life, X-rays and color panels rotating together.

“It always felt like photographers had to photograph, painters paint, and sculptors sculpt. I don’t think art has to be so confined.”

Photopainting: Deadend Street (1978)

A photography panel is a realistic scene of one second in time, and a painting panel can be abstract and atemporal — as a result, the combined panels become one second against eternity.

It always felt like photographers had to photograph, painters paint, and sculptors sculpt. I don’t think art has to be so confined. Now many people combine photography, painting, and sculpture, but when I did it 50 years ago people got confused. I believe there can be many resolutions.

Photogram: Attractants Positive (1995)

From 1967 to 1980, I was doing photo paintings, moving away from strict photography by combining it with painting or a sculptural element. These pieces kept getting rejected for shows, so in 1980 I thought I’d return to photography’s simplest, earliest position: the photogram. I started with photograms of little things around the house, but then somebody gave me a flower bouquet, so I made some photograms using pieces from it. I loved the contours of these flowers, so I started doing lots of flower photograms.

Kunié Sugiura: Photopainting is on view from April 26 through September 14, 2025, on Floor 3.