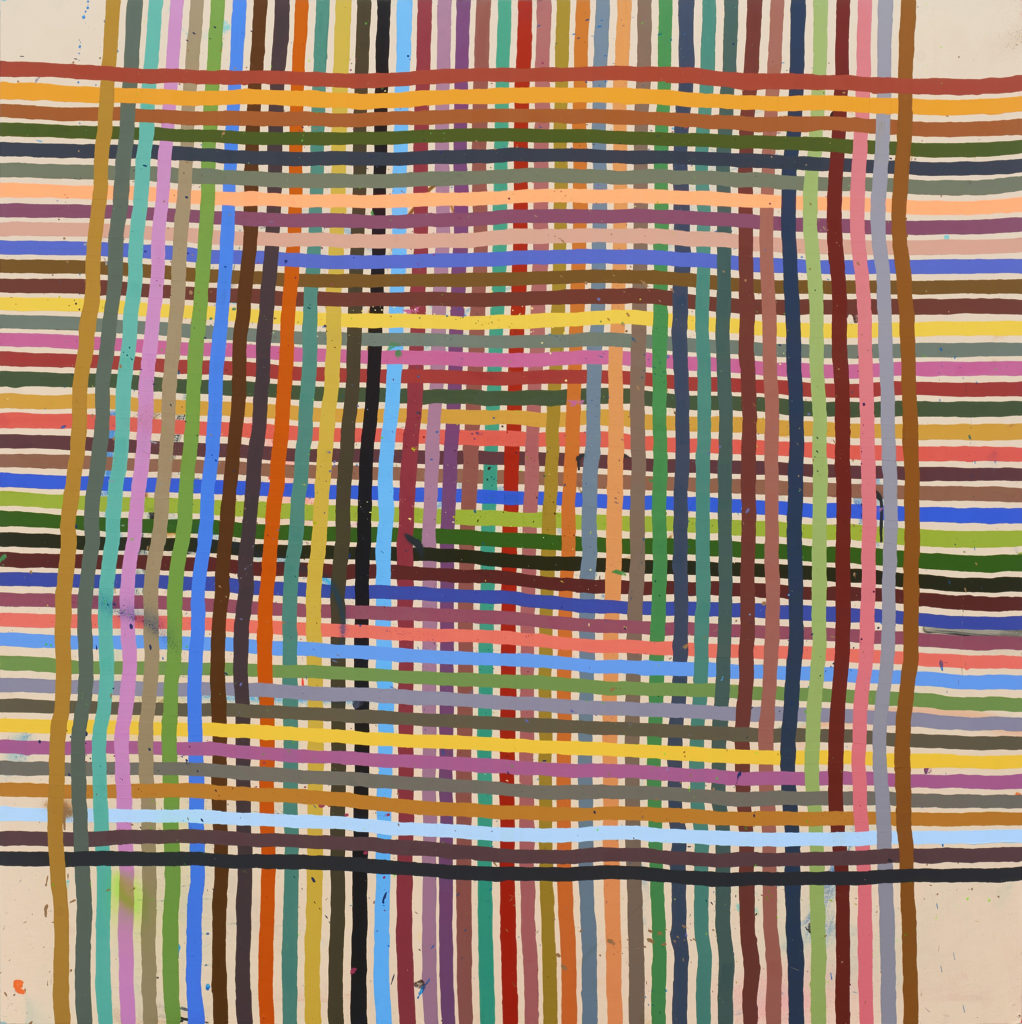

Alicia McCarthy, Untitled, 2017; collection of Joachim and Nancy Hellman Bechtle

Alicia McCarthy’s compositions comprise intricate communities of lines, colors, and forms. They are constructed through a repetitive process of seemingly simple mark making, a sensitivity to hue and pigment density, and an openness to the distinct character of each gesture. An accessible quality permeates her humble materials and vibrant, organic geometries, whether painted or drawn. The decisions she makes in the studio reflect how she navigates everyday life, as well as the many Bay Area histories that she has been part of since the early 1990s.

Best known as a key figure in the legendary Mission School, McCarthy has been associated with a long lineage of artist-based communities. At Humboldt State University in Arcata, California, she met Harrell Fletcher and Virgil Shaw, who ignited her interest in working beyond gallery walls and strengthened her connections in the Bay Area. Later she was influenced by several generations of artists who studied and taught at the San Francisco Art Institute, including Joan Brown, David Park, Manuel Neri, Richard Shaw, and Irène Pijoan, for whom she was a studio assistant.1 Jay DeFeo’s enigmatic painting The Rose (1958–66) was hidden behind a wall at the school; according to McCarthy, “You couldn’t be a student or a painter without feeling its intensity like a haunting ghost-like presence.”2 She became fast friends with fellow students Ruby Neri and Barry McGee, as well as with Margaret Kilgallen and Chris Johanson, who weren’t enrolled but spent time on campus. Though their individual interests extended beyond the group, including into queer and punk communities and small experimental art venues, Johanson, Kilgallen, McCarthy, and McGee would be forever linked by critic Glen Helfand’s characterization of them as progenitors of a craft and folk art, DIY aesthetic rooted in the streets of San Francisco’s Mission District.3

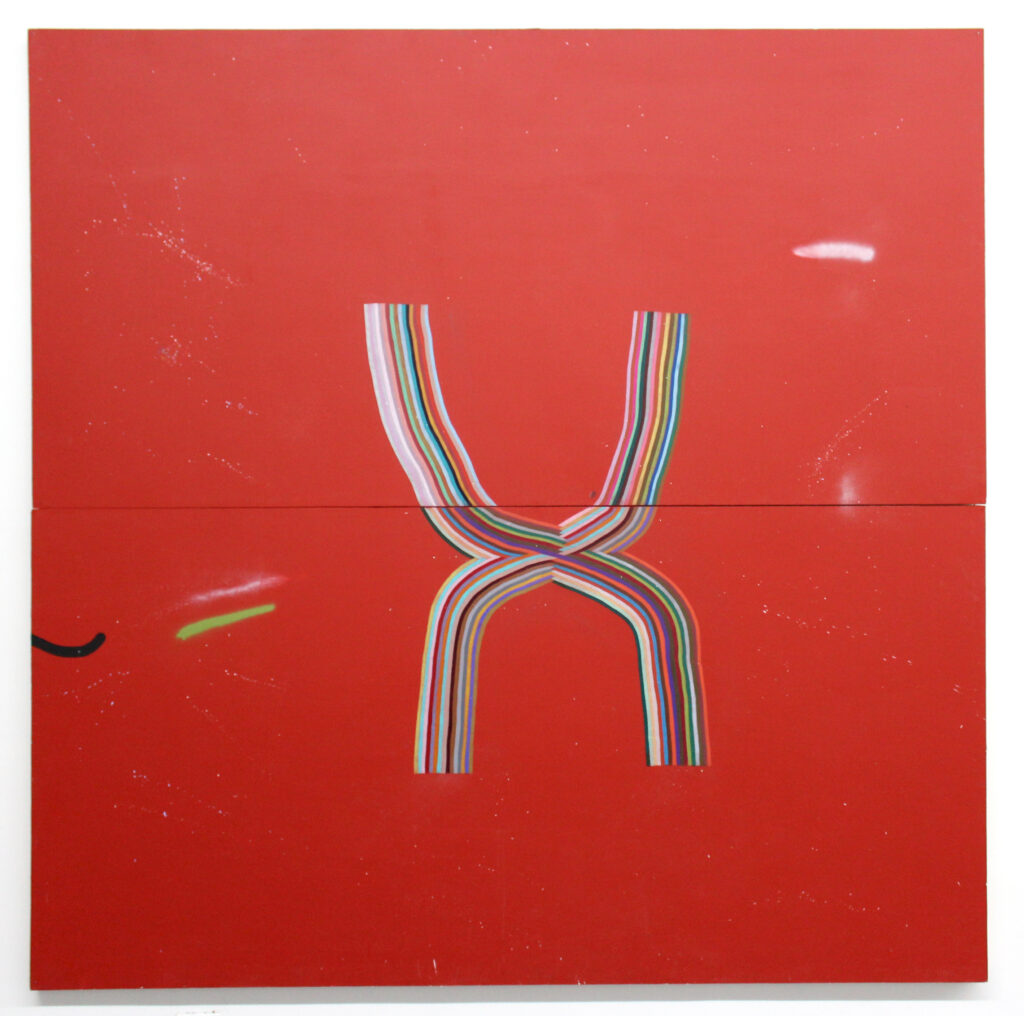

Alicia McCarthy, Untitled, 2015; private collection

These communities have shaped McCarthy’s collaborative sensibility and preference for modest materials. Focused on the act of making, she has long eschewed overwrought presentations. At the beginning of her career she often installed her paintings and drawings in the corners of galleries, included intentionally misspelled words, and left her work unsigned. “Disturbed by the amount of waste”4 and naturally drawn to things that are cast off, she frequently took found objects—many made of wood—and covered them with house paint, which she also applied directly to walls both inside and outside of galleries. She treated exhibitions, even solo shows, as spaces to share with other artists. Today McCarthy still applies house paint to wood surfaces, but now she buys new panels, high-quality colored pencils, and water-based spray paint. She continues to embrace drips and splatters and to incorporate her friends’ work into her exhibitions, though in smaller quantities. Her installation at SFMOMA features drawings by ORFN (Aaron Curry), who passed away from cancer in December 2016. McCarthy’s inclusion of his art celebrates his prolific and deeply influential presence in the Bay Area.

McCarthy’s process mirrors the creativity and individuality celebrated by the many communities she has been part of. She has found infinite freedom and variation within a rule-based practice, forming intricate patterns through basic tropes of grids, what she calls “weaves,” curves akin to rainbows, and color blocks or bars. One could spend hours trying to determine how she assembles them. She approaches both her “positive” textile-like images, with filled-in lines, and “negative” weaves, with filled-in ground (see cover), the same way: beginning in the middle and expanding outward, interlacing strands over and under until she reaches a point near, but not at, the edge. For her SECA installation McCarthy introduced a new support into her repertoire—interested in translucency, she translated a combination of her negative and positive weaves onto large sheets of Plexiglas. Unable to adjust missteps on this unforgiving surface, she had to learn quickly how her usual materials would react to an unfamiliar ground.

An undeniable energy imbues McCarthy’s work—a buoyancy that bursts and continually shifts across the surface. She builds up the backgrounds of her painted compositions over several days to set the right stage for the interactions of her lines and colors. Her hues are always unique: a pigment is never used directly from the tube but is mixed just before application and determined by the tone that preceded it. She explains, “Colors next to each other vibe so differently. You could immediately go in a different direction.”5 Her structured practice thus allows her to effectively experiment with juxtaposition and density. Careful and considered, her paintings and drawings are reminiscent of works that employ modernist color theory—particularly those of Bauhaus artists Anni and Josef Albers—yet her choices are instinctual and resolutely nonacademic.

Alicia McCarthy, Untitled, 2016; collection of Cassandra and Paul Hazen

McCarthy brings an off-kilter quality not only to her palette but also to her lines, which never feel precious or overly worked. They are determined as they meander from one end of the support to the other or as they form a section of a curved band. She highlights the imperfections of her organic gestures and does not use tape as a guide. Her sprayed marks have an inherent fuzziness as they intermingle, often with more empty space around them than her painted lines. When one composition is finished, she removes it from her studio as she proceeds on to the next.

McCarthy’s sequenced taxonomies provide solace from the chaos of the outside world through their focused repetition. Yet she also finds inspiration in her surroundings: her use of wood connects to San Francisco’s wood-based architecture; her palette and rainbow-like patterns draw on the light and atmosphere of the area. She has said, “I want my work to reflect all the beauty and pain of everyday life. All woven together and interconnecting to create [images] based in line and color.”6 Made up of the people and places around her, McCarthy translates the energy and emotion she feels into a sincerely human form of abstraction.

Notes

- McCarthy also cites the influence of Katherine Sherwood, her professor while studying for her MFA at the University of California, Berkeley.

- San Francisco Art Institute, Energy That Is All Around, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2014), 22.

- See Glen Helfand, “The Mission School: San Francisco’s Street Artists Deliver Their Neighborhood to the Art World,” San Francisco Bay Guardian, August 7, 2002.

- Alicia McCarthy, interview by the author, January 24, 2017. Exhibition files for 2017 SECA Art Award: Alicia McCarthy, Lindsey White, Liam Everett, K.r.m. Mooney, Sean McFarland, SFMOMA Department of Painting and Sculpture and Department of Photography.

- Ibid.

- Alicia McCarthy SECA application, July 1, 2016. Exhibition files for 2017 SECA Art Award: Alicia McCarthy, Lindsey White, Liam Everett, K.r.m. Mooney, Sean McFarland, SFMOMA Department of Painting and Sculpture and Department of Photography.