For over 150 years, the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) served as a vibrant creative hub for artists. After the school’s 2022 closure, former longtime SFAI librarians Becky Alexander and Jeff Gunderson worked to create the SFAI Legacy Foundation + Archive to preserve written and printed records, photographs, and moving images documenting its storied past.

Some of these materials are coming to SFMOMA this summer for People Make This Place: SFAI Stories, an exhibition featuring collection works in a variety of media from the 1940s through the 2010s by former students and faculty. The exhibition title quotes artist, alum, and longtime faculty member Dewey Crumpler’s 2022 SFAI commencement speech invoking the individuals who shaped the spirit of the school.

In the below interview conducted by SFMOMA Director of Library and exhibition co-curator David Senior, Becky Alexander illuminates SFAI’s legacy in depth.

David Senior: I like the term “memory work” to describe the role that librarians and archivists have in communities and institutions documenting our cultural memory of places, events, and individuals. Can you describe how the SFAI Legacy Foundation + Archive came about?

Becky Alexander: It’s pretty remarkable that all the pieces fell in place to get us where we are now with the SFAI archives, starting with the fact that so much material documenting the school and its history was saved in the first place! It took a lot of organization and foresight—qualities that, to be honest, I haven’t always associated with SFAI—to save and preserve the contents of the collections. And it certainly took a combination of luck and generosity for the SFAI Legacy Foundation + Archive to come to be.

As it became clear that the school truly would close, the project felt more crucial than ever. Right as things started to fall apart, we got the news that a grant proposal we had written to the National Endowment for the Humanities to work on the archives had been accepted. Through the chaos of the ensuing months, we were able to hold on to the idea of continuing with the grant-funded work as a guiding light.

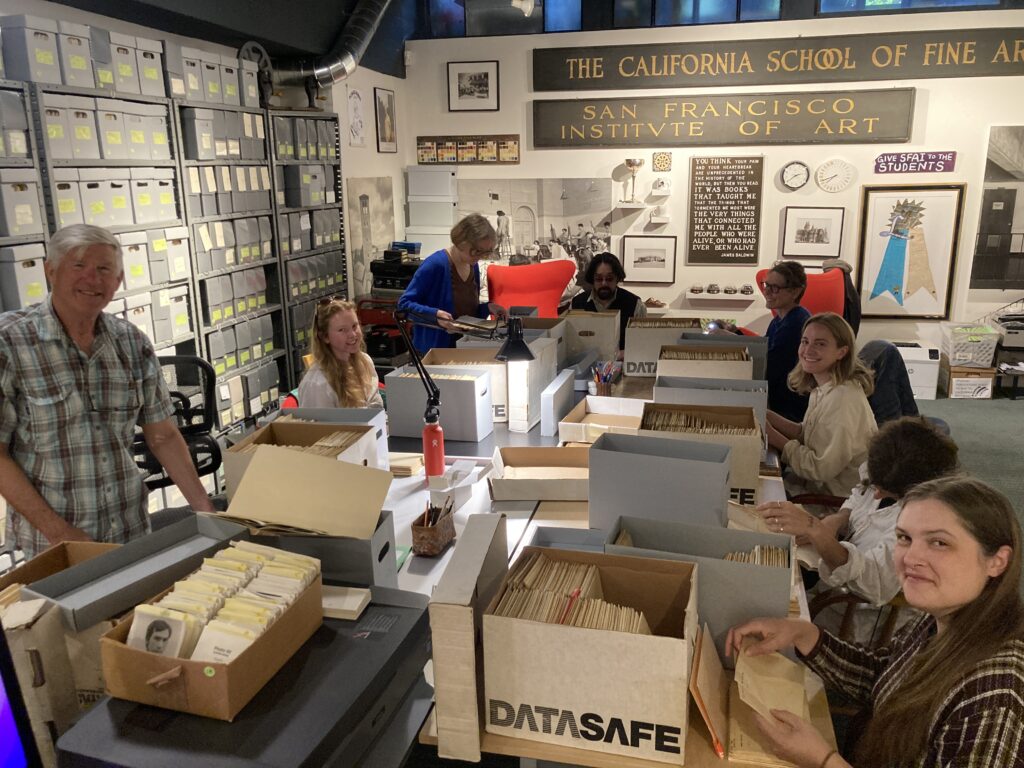

But you can’t give a grant to an institution that no longer exists! It took about a year for the SFAI Legacy Foundation + Archive to set itself up as a new nonprofit that could receive the grant. Moving the archives to a new off-site home on Hawthorne Street also took the generosity of kind donors and the hard work of the amazing SFAI Alumni group, who put on a big fundraiser and auction, The Spirit is Alive, which helped cover costs that weren’t covered by the grant, including rent on the new space. We also had packing and box-labeling help from organizationally minded friends, including some top-notch librarians from SFMOMA!

DS: Can you describe the historical connections between the school and SFMOMA that can be traced through the SFAI archive?

BA: Both SFAI and SFMOMA were offshoots of the San Francisco Art Association (SFAA), which was founded in 1871 by a group of artists and supporters to promote the city’s nascent art scene. Two of its goals were to start a school and to hold exhibitions. The school started as a ramshackle operation on Pine Street, then was gifted the Mark Hopkins Mansion on Nob Hill, which unfortunately burned to the ground in the 1906 earthquake and fire. It ended up in a newly constructed building at 800 Chestnut Street in 1926. On the museum side, the Art Association’s exhibitions program started small, then picked up steam after the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, when the fair’s Palace of Fine Arts building was saved from demolition for the purpose of housing an SFAA-run art museum.

The museum, then called the San Francisco Museum of Art, moved to the War Memorial Veterans building on Van Ness Street in 1935, eventually adding “Modern” to its name in 1976 and moving to its current location on Third Street in 1995. It formally split from the Art Association in 1935, but the connection with the school remained strong. In 1934, Grace McCann Morley, the museum’s director, had an office at the school and taught art history there. The museum even had an Art Association Gallery where SFAA artists showed their work. The school and the museum collaborated on events like the 1949 Western Round Table that brought in big names like Marcel Duchamp, Mark Tobey, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Gregory Bateson to debate the merits of modern art.

The Art Association eventually faded away and was reabsorbed into SFAI in the 1960s. As a result, the SFAI archives hold a lot of material related to both the school and the museum. Most of the very earliest Art Association records burned in the 1906 earthquake and fire, but the original minute books got saved — enormous, leatherbound volumes written in long-hand that contain great documentation of those days, like Eadweard Muybridge’s exhibition of his famous trotting horses, which took place at the school.

DS: Did your work over the past year reveal any unexpected materials or stories?

BA: This is one of the best things about the job. Sometimes it’s as simple as opening an administrative folder and finding a treasure trove. Recently, Jeff found a fantastic set of faculty ID photos from 1972 containing a whole bunch of familiar faces, looking amazingly shaggy-haired and youthful.

At other times, the surprises come from looking through things we’ve seen many times, but more closely, or with new context, or at a higher resolution. Zooming in on scans of slides or contact sheets can reveal so much: the little dog house in the yard of the Chestnut Street campus or the reflection of artist Joan Brown’s face in the mirror of a 1958 ceramics class.

DS: Who are individuals that stand out to you as SFAI heroes?

BA: Some of my SFAI heroes will come as no surprise to any alum, like the filmmaker and teacher George Kuchar, who I think embodied the best of SFAI. George was endlessly generous as a teacher and a person and had a subtle comedic genius running below the surface of everything he did, artistically and otherwise.

Carlos Villa, who has been posthumously getting well-deserved recognition in recent years, is a hero for similar reasons. Villa would tell a story from his student years of a professor telling him there was “no such thing as Filipino art history.” Villa set out to prove him wrong in the subsequent decades, showcasing and engaging with the diverse cultural voices within contemporary art and art history.

There are so many artists who were deeply influential at the school and in the San Francisco arts scene. Jay DeFeo, Bernice Bing, and Joan Brown are a few personal favorites. The list of people who deserve more attention is also long. It includes the artists’ model and bonne vivante Flo Allen, who founded the Bay Area Model’s Guild and wrote a “Flo Sez” column in the local Black newspaper the Sun Reporter; Bernard Mayes, the gay Anglican priest who taught in the humanities department and who, seeing the struggles faced by members of San Francisco’s gay community, started the first suicide hotline in the U.S.; and Theophilus Hope d’Estrella, a deaf artist who became a student at the school in the late 1800s, despite the narrow-minded resistance of its first instructor, Virgil Williams (in the end the two formed a life-long friendship).

I would also nominate the crew of students, faculty, and staff who were there through the school’s waning days as SFAI heroes. Against all odds, SFAI continued, to the bitter end, to be a place that felt collectively devoted to the project of helping students grow as artists.

DS: How did the school evolve over its history to support new forms of art making?

BA: SFAI was a place where artists — and by extension new artforms — could flourish. The school provided the conditions in which new art could grow: space, time, and the collectively held belief that exploration and experimentation are of intrinsic value. Longtime SFAI instructor/artist/administrator Fred Martin used to describe the school as a monastery; a place where art making could be sheltered from the pressures of the outside world. Paul Kos, artist and instructor of performance, video, and new genres, called it a laboratory, where experimentation wasn’t just allowed, but was the whole point.

People often point to the generative atmosphere of the postwar period, when former San Francisco Museum of Art curator Douglas MacAgy became the school’s director, bringing in Ansel Adams to start the first fine arts photography program, Sidney Peterson to start an experimental film program, and Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko to teach painting. It didn’t hurt that the school was flush with G.I. Bill money at that point. You can frame this as a story of good leadership, but I think it was less a top-down approach, and more about having the presence of mind to bring in interesting people and let them do their thing.

Another classic SFAI story is that the school sold its collection of Muybridge prints in 1980 to buy equipment for a new performance-video department, ushering in a period of groundbreaking work. The story illustrates that the school was open to giving something up to start something new. Part of growth is risk-taking and letting go.

The school benefited enormously from the passion, energy, and diversity of people and cultures that surrounded it. The social and political forces in San Francisco were always at play at the school, whether it was the 1930s labor movement, the Civil Rights movement, the countercultural movements of the 1960s and 70s, the Black Power and Red Power movements, movements for Asian American civil rights, and the LGBTQ rights movement.

We often talk about the idea of “fertile ground,” as referenced in the 2014 exhibition Fertile Ground: Art and Community in California, which was co-organized by SFMOMA and the Oakland Museum of California and touched on many pieces of the school’s history. You need all the elements in place (sunlight, water, good soil), and then you step back, and something grows. There is a relief carved by the artist Jacques Schnier above the fireplace at the former Chestnut Street campus library called The Soil that embodies that idea. This is the tragedy of losing the school — the loss of that fertile ground where new things could grow and blossom.

People Make This Place: SFAI Stories is on view July 26, 2025, through January 4, 2026, on Floor 2.